London is notoriously a crib for the wonderful, culturally fascinating, and innovative.

The multi-ethnic capital is home to almost nine million people and has a huge influence on all kinds of sectors, from finance to arts, to fashion and pop culture.

As well as being the historical home of Guinness World Records, London also saw the rise of many incredible artists, like The Beatles. The iconic Liverpool group recorded in London the hit song "Across the Universe", which became the first song to be beamed into deep space in 2008, to celebrate the 50th anniversary of NASA’s founding and the 40th anniversary of the song being recorded.

The British capital is also the record holder for most Olympic Games hosted by a city: a grand total of three. First in 1908, then in 1948, the first games since 1936 and World War II, and again in 2012.

But some records are slightly less famous, although no less fascinating.

So, without further ado, hop onboard a double-decker bus and embark with us on this tour of London… through some of the city’s quirkiest records.

Every day, the London Underground hosts an incredible number of tourists, workers, and commuters.

A symbol of an ever-existing routine for many, "The Tube" is much more than just a system of railways and stations: it’s the first and oldest underground railway system in the world.

The first railway plan was proposed in the 1830s, although the Metropolitan Railway would be granted permission to start the work some years later, in 1854.

In 1855, a test tunnel was built in the small town of Kibblesworth, selected for the test thanks to its geological similarities with the capital.

The first section of the London Underground opened officially on 9 January 1863, with the first passenger journeys beginning the following day – a Saturday. The initial stretch of that very first line ran 6 km (3.73 miles) between Paddington and Farringdon Street, and used gas-lit wooden carriages hauled by steam locomotives.

On that very first day, the newborn underground system carried 38,000 passengers.

A world-changing introduction that, without a doubt, marked the beginning of modern commutes in the British capital.

In the following centuries, a true subterranean realm stemmed from those very first 6 km.

Today, according to the official website, the London Underground counts 11 lines covering 402km and serving 272 stations.

Ever since the system has grown and adapted to the city, becoming an essential part of the very fabric of London.

Today, the train service handles up to five million passenger journeys every day: a striking difference in figures if compared to that first Saturday journey that kicked off The Tube's history.

“At peak times, there are more than 543 trains whizzing around the Capital,” writes Transport For London on their website.

A "cut and cover" system was used to build the line, created by digging up streets along the route. The tracks would be laid in a trench and then re-covered with a brick tunnel and new upper road surface.

Many people use this service every day, and some others even broke records on the London Tube!

That's the case of Steve Wilson (UK) and AJ, who broke the unusual record for the fastesttime to travel to all London Underground network stations. The two travelled through the entireness of the London Tube and touched base in each and every station within the incredible time of 15 hours, 45 minutes and 38 seconds, completing their urban adventure in May 2015.

Postal codes are part of our everyday life today, but did you know they were first introduced in London?

The first postal system, which would evolve into what we know today as ZIP codes, was used for the very first time in 1857 in the capital, designed by Sir Rowland Hill (UK).

At the time an urgent postal reform was rendered necessary by the rapid growth of the city area, which in the 1840s saw an increase in population and a never-seen-before urban development due to industrialisation. London was growing, and so were its needs.

To increase the efficiency of the local postal service, London was then divided into 10 postal districts: EC (East Central), WC (West Central), N, NE, E, SE, S, SW, W, and NW, each covered by the national postal service.

As it’s easy to imagine such divisions were based on the compass points, with N standing for “North,” W for “West” and so forth.

The system was refined in the following years and, with World War I, sub-districts were added to the urban plan.

London’s example was followed by other large cities, such as Manchester in 1867.

However, even if London used the very first postal code, the first form current postcode – a mixture of letters and numbers that can be decoded by a machine to allow faster sorting – was first used in Norwich, UK, in October 1959.

Another change was required due to the increase in mail volumes after World War II, and the municipality of London was forced to amp up the scale of its postal system. On that occasion, a nationwide postcoding scheme was introduced, enabling mail to be sorted automatically by machine.

Although a certain form of postcode system had been in use in the US since the Roaring 20s, the massive scale of letters exchanged during World War II forced the United States to adopt a postal system similar to the one in use today.

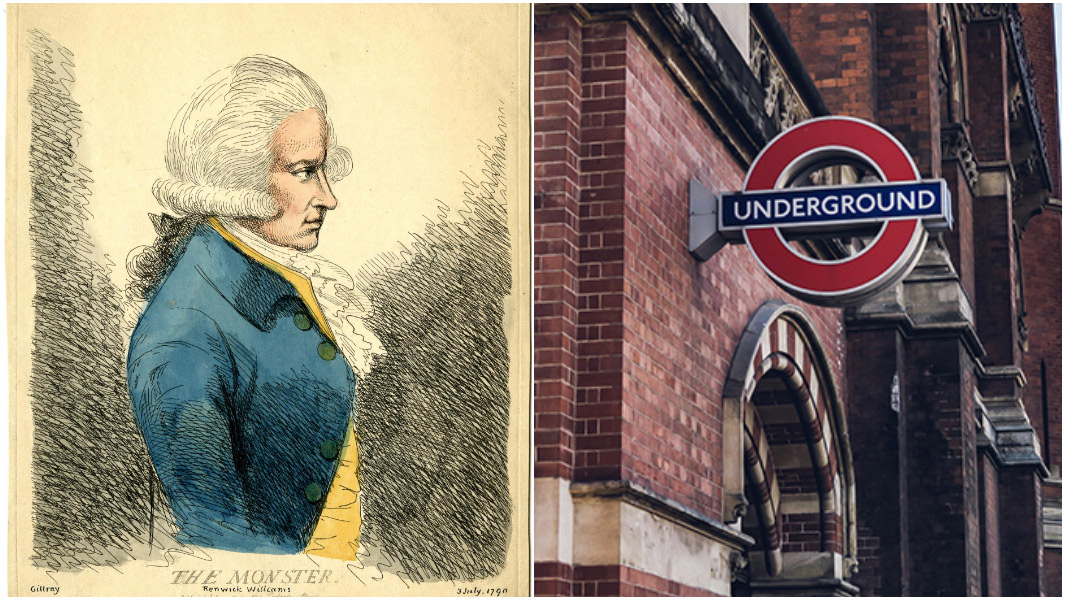

Widely known as the London Monster, this serial stabber is known to be the first ever documented serial stabber in history. Perhaps less famous than Jack the Ripper, who would terrorize the Whitechapel district almost a century later, in the autumn of 1888, the deeds of the London Monster are no less horrendous.

This serial stabber was active around the year 1790 in the British capital, and reports date the first attacks as early as 1788.

The maniac and serial stabber was at large in central London, terrorizing his victims through acts of physical and verbal abuse. His presence and attacks caused distress to all kinds of women – although his favourite victims seemed to be wealthy gentlewomen.

He often approached his victims in the streets and slashed their skirts, then stabbed them in the buttocks or the face after luring them in with an excuse. He would also scare the victims while shouting obscenities.

It is reported that the "London Monster", as he was called, claimed at least 50 victims.

In June 1790, after a lady called Anne Porte claimed to have identified her attacker, a Welsh artificial flower maker named Rhynwick Williams was arrested as the Monster. After his imprisonment the attacks diminished, although the evidence against the man would be considered rather shaky by a modern jury.

Some historians question if the London Monster even existed at all, and others wonder how many of his crimes were due to emulators or similarly-operating maniacs.

But that’s not the only curiosity about the “London Monster” case: the London Monster-mania of 1790 is also the earliest recorded instance of copycat crime and, to this day, it leaves behind many unanswered questions.

Who doesn't love ice skating?

It’s one of those activities that both children and grown-ups enjoy, and it has become one of the most recognizable Christmas sports.

While frozen rivers, lakes and ponds have been used for recreational, amateur and professional ice sports for centuries, the British capital counts two historical, record-breaking ice rinks that marked a new era for those who wanted to enjoy this past time in the middle of the city.

The year was 1841, and the joint efforts of London-based inventor Henry Kirk and architect William Bradwell created a space dedicated to one of the first – and still greatly loved – winter entertainments in the world.

Such is the earliest successful attempt to create the first artificial ice rink, also known as the “Frozen Lake”: a quirky and innovative invention that would allow Londoners to ice skate all-year round.

The ice rink, initially meant for recreational purposes, was opened on the grounds of Jenkins seed nursery in London, UK, on 13 December 1841. To attract investors, Kirk and Bradwell invited England's best skaters to test out the rink.

The area was created before the invention of any technology for freezing water, and the 3.6 x 1.8 m (12 x 6 ft) rink was, in fact, not made of ice!

The surface was composed of Kirk's patented concoction of sulphur salts mixed with water and "hog's lard, to render it more slippery". The use of copper sulphates gave the "ice" a bluish hue, and Bradwell's designs for the room recreated a "very picturesque landscape".

However, it’s said that the smelly pork fat was, by some accounts, off-putting to visitors.

Only a few years later, the Italian-born inventor John Gamgee (UK, b. Italy, 1831–94) opened the first mechanically frozen ice rink.

The rink was inaugurated in London on 7 January 1876 – thirty-five years after Kirk and Bradwell’s artificial ice rink.

The so-called “Glaciarium” was opened in Chelsea, inside a canvas tent.

Attracting a wealthy clientele and operating on a membership-only scheme, by March of the same year the rink was enlarged from 5 x 7 m (16 x 24 ft) to 12.2 x 7.3 m (40 x 24 ft). Gamgee also installed an orchestra gallery with live music (courtesy or a local 'promenade band') and decorated the walls of the tent with picturesque views of the Swiss Alps.

Soon after, the veterinarian, inventor and entrepreneur also opened two more rinks in Charing Cross, London, and Manchester.

Thanks to his job as a veterinarian, Gamgee soon became fascinated with methods of freezing meat for long journeys at sea. Later, in 1870, he first patented a freezing method that he would later adapt to create his Glaciarium.

To create the ice rink, inside the canvas tent Gamgee laid a concrete floor measuring over which he spread an insulating layer of earth, cow hair, tar and wooden planks.

On top of that surface, he laid copper pipes through which a mixture of glycerin, ether, nitrogen peroxide and water was pumped by a steam engine. Lastly, water was then poured on top to a depth of around 5–8 cm (2–3 in).

The water, much different from Kirk’s pork fat, would eventually freeze and provide a solid surface for the visitors' entertainment.

The Zoological Society of London (also known as ZSL) was founded in 1826, and in 1928 founded the oldest scientific zoo ever established.

Starting from 1831, the then newly-established scientific zoo (situated in the northern edge of Regent's Park) housed the animals previously stationed at the Tower of London menagerie. The zoo's collection and scientific relevance, as well as its fame, grew exponentially over time - to the point that a second zoo was opened, the ZSL Whipsnade Zoo in Bedfordshire, to house the bigger specimens such as elephants or giraffes.

Did you know that you couldn't always visit the London Zoo?

Originally intended as a collection where scientific study could bloom, the zoo was opened to the public in 1847.

In July 1996, the zoo's collection comprised of 14,494 specimens, respectively housed in the London historical location within Regent's Park and at the more spacious area of Whipsnade Park, Dunstable, Bedfordshire.

Ever since the zoo furtherly developed and grew, and it now comprises almost 20,000 individuals with 673 species. It is also known to be the first zoo with a children's zoo, established in 1938.

However, that is far from all.

Different areas of the London Zoo also hold more historical "firsts", making it a place that pullulates with records:

The first public aquarium (then known as an Aquatic Vivarium) was commissioned on 18 February 1852 by the Council of the Zoological Society of London and opened the following year, in May 1853.

It’s incredible to think that the London Zoo aquarium precedes the word itself: when the “Fish House” was built, the term aquarium didn’t exist yet.

The word, initially unpopular among scholars, would be coined only the year after by English naturalist Philip Henry Gosse with the publication of his book The Aquarium: An Unveiling of the Wonders of the Deep Sea (1854).