Andy Green: Fastest car (land-speed record)

As the speedometer crept up past 350 mph (560 km/h), Andy Green OBE realised that his car was swinging out of control. Each tiny movement of the steering wheel created a wobble that required another movement to correct. He hit the brakes knowing that if he couldn't get this under control, his team's world record hopes were over.

It was May 1997, and the 34-year-old British fighter pilot was, technically at least, on holiday. He'd saved up his time off to come out to a desolate, sun-baked mudflat near the village of Al-Jafr in Jordan. Here he was driving – or perhaps more accurately, piloting – a 10-tonne (11-US-ton), 14.5-m-long (48-ft) jet-powered car called Thrust SSC. Along with a team of sunburned, dust-covered engineers, he was trying to iron-out the last few problems with the vehicle before shipping it off to the United States for a world record attempt.

That morning, as the engines spooled down and the car slowly drifted to a stop, Andy thought to himself "I think this project has just finished. The car’s unstable. I think we’re stuffed." That night, he stayed up thinking it over. He decided the only thing to do was the "bully the car into being stable" – making constant, tiny adjustments to maintain stability, saving larger, less frequent adjustments for when he actually needed to steer the car. It was a process he likened to balancing a pencil vertically on the tip of his finger.

The trick worked, and over the next few runs the car was brought under control. On 3 Jun 1997 – the team's last day of testing – Andy took Thrust SSC up to 490 mph (788 km/h), or about as fast as the car could go in the limited space of the Al-Jafr mudflats. The crisis had been averted, and Thrust SSC was on its way to a world record.

From air to land

Andy Green had first gotten involved with this strange project in Jun 1994, after his interest was piqued by a headline in the paper that read, "Wanted. High-speed driver to break the sound barrier". He'd been fascinated by the land-speed record since childhood, and had followed British driver Richard Noble's campaign that had raised the mark to 633.468 mph (1,019.467 km/h) on 4 Oct 1983, driving the Thrust SSC's predecessor, the Thrust2. Now, Noble was putting together a team to go after the last great land-speed record milestone – the sound barrier – and he needed a driver with test-pilot experience behind the wheel.

Andy knew his experience flying supersonic fighters put him in a strong position, and, having recently performed a 111-m (364-ft) bungee jump for no reason other than sheer daredevilry, he knew that the warning against "those of a nervous disposition" did not apply. The role also appealed to his patriotism, as it was a chance to claim a world record for Queen and country – a British car with a British driver – and to continue the Royal Air Force's historic association with record-breaking.

In some ways Andy seems like a throwback to the gentleman racers of the 1920s and 1930s. He studied at Worcester College, Oxford, where he excelled at, well, more or less everything he tried – rowing in the Men's VIII, flying in the Oxford University Air Squadron and earning first-class honours in mathematics. Within a year of his graduation in 1983 he was promoted to Pilot Officer in the Royal Air Force and began training for a role in a jet fighter squadron.

By the time he saw the advert in the paper, Andy was an RAF Flight Lieutenant flying the supersonic Panavia Tornado. In his spare time he tinkered with motorbikes, raced bobsleds and ran marathons. Racing land-speed records cars was, to him, just another fun hobby – something he was happy to do simply for the satisfaction of having done it.

When Andy joined the team, work on the car he would one day drive was well under way. Richard Noble and his engineers had acquired four Rolls-Royce Spey jet engines – two of which were factory-fresh experimental models called Mk 205s. These were the engines used in the supersonic F-4K Phantom fighter jet. Thrust SSC (the SSC stood for "supersonic car") was essentially designed around these two massive engines, with the aerodynamicists settling on a design that looked a lot like a wingless fighter jet.

Combined, the engines produced 182.3 kilonewtons of thrust (41,000 lbf), rising to 222.4 kN (50,000 lbf) for the 205s. This was easily enough power to break the sound barrier, the big problem was going to be controlling it. After testing and abandoning many other designs, the team settled on an unusual rear-wheel steering set-up, where the front two wheels would be fixed just outboard of the jet intakes, while the rear two pivoting wheels would be arranged in a sort of staggered tandem – one in front and slightly to one side of the other – on the car's centreline.

To test this arrangement, the team's engineers welded together a very strange Mini Cooper. This car looked like a regular mini up front, but instead of the usual rear wheels it had a metal truss extending about a car's length out of the back with two wheels attached, one in front of the other. In addition to proving the steering concept, this funny-looking testbed gave Andy a chance to practise this unusual, rudder-like arrangement.

The fine-tuning of Thrust SSC's design was done on the fly. During tests in Sep 1996 and May 1997 (using the weaker Mk 202 engines), the team would alternate between test runs and periods of feverish activity, where they machined new parts, changed designs and reprogrammed control systems. After Andy's 490-mph run, it was decided that the car was finally ready, and the team started work on shipping everything out to the Black Rock Desert in Nevada, USA.

On the morning of 15 Oct 1997, Andy Green once again climbed into the cockpit of Thrust SSC. It had been a long month of near-misses and disappointments. He was already the land-speed record holder – having reached 714.144 mph (1,149.303 km/h) during a pair of runs on 25 Sep – but no one wanted to go home without having broken the sound barrier.

In front of him lay 14 mi (22.5 km) of painstakingly manicured alkali flats, every inch carefully graded and checked for stones and debris. Extending from the tip of Thrust SSC's nose to the horizon was a white painted line. In a few minutes' time, this would be Andy's only point of reference as his car tore across the desert – everything else would be either blurred by the speed or obscured by the massive engine nacelles rising on either side of his cockpit. Somewhere between him and the horizon was a pair of measurement points, one mile apart, which marked off the section that would count towards the speed record.

At 9.08 a.m., Andy fired up the engines and Thrust SSC started moving, very slowly. Because the intakes were calibrated for high speeds, 0 to 100 mph ticked past in a relatively leisurely 20 seconds. Once the airflow picked up, however, Andy was able to put his foot down and the car leaped forward, accelerating by a further 100 mph every four seconds and pinning him back in his seat.

From his vantage point, Andy couldn't be sure whether this run was going better or worse than the others. All his energy and attention was concentrated on the task of keeping the car under control, which was proving to be even harder in Black Rock than it had been in Jordan. As the car accelerated, automatic systems would shift the aerodynamics around, adjusting the suspension and moving control surfaces. This was vital – enough downforce to maintain control at 200 mph would have rammed the car into the ground at 700 mph – but it meant that every time they went faster, Andy had to contend with new challenges.

Still, he'd seen the machometer tick past the red line that marked Mach 1, so he a good feeling when he triggered the braking parachute and began the 6.5-mi (l0.4 km) deceleration that would bring him to a stop at the turnaround spot.

When the official timing data came in, the two runs were averaged to produce a new land-speed record of 763.035 mph (1,227.985 km/h) or Mach 1.02. Andy had not only smashed his own record, he'd also set the first supersonicland-speed record.

After the press attention died down, Andy went back to his day job. After all, this was all just something to do on his holidays – a gentleman amateur wouldn't dream of going professional. Not long after the record attempt he was promoted to Squadron Leader, and in 2003 was made Wing Commander. However, the world of land-speed records still had a certain appeal...

Life after Thrust

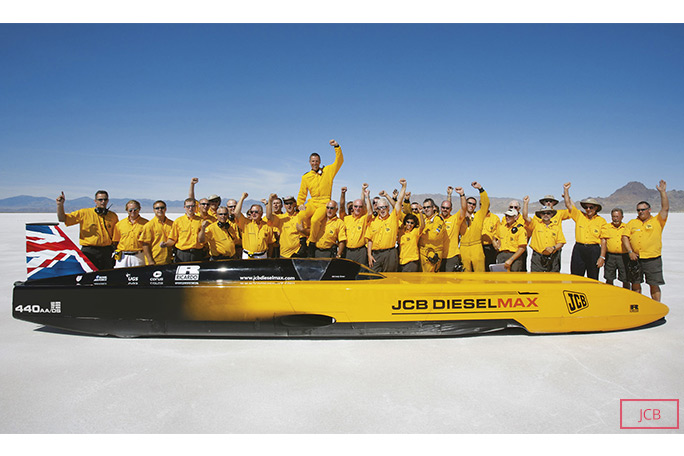

In 2005, Andy was approached by the chairman of British construction-equipment builder JCB. They had a new diesel engine that could produce 750 hp (560 kW) with the right modifications, and they wanted to have a go at the diesel-engined land-speed-record, which at the time stood at a "mere" 253 mph (407 km/h).

Andy agreed to drive for them, provided they used at least two of these engines and made a proper go of it. Thus on 22 Aug 2006, Andy earned his second GWR title, breaking the diesel land-speed record at the Bonneville Salt Flats in Nevada, USA, with a two-way average time of 350.092 mph (563.418 km/h). Fast as that is, it was nowhere near the limits of the car's power. That speed was merely the fastest the tyres could withstand – Andy never even got the car into top gear. With the right tyres, he estimated it could easily make 450 mph (724 km/h).

Today, Andy is associated with Bloodhound LSR – a British land-speed-record project that aims to make the biggest leap forward in the history of the discipline, moving the record from 763 mph to over 1,000 mph (1,609 km/h). The project has been beset with financial problems, causing many delays, but the car is now built and nearly ready for its chance at the world record.

On 16 Nov 2019, Andy piloted Bloodhound to 628 mph (1,011 km/h) during tests at the Haskeen Pan in South Africa. This means that Bloodhound, which hasn't even been fitted with its hybrid-fuel rocket booster yet, is already one of the top 10 fastest cars of all time. As a result, it seems fair to assume that Andy Green will be breaking records again in the not-too-distant future.

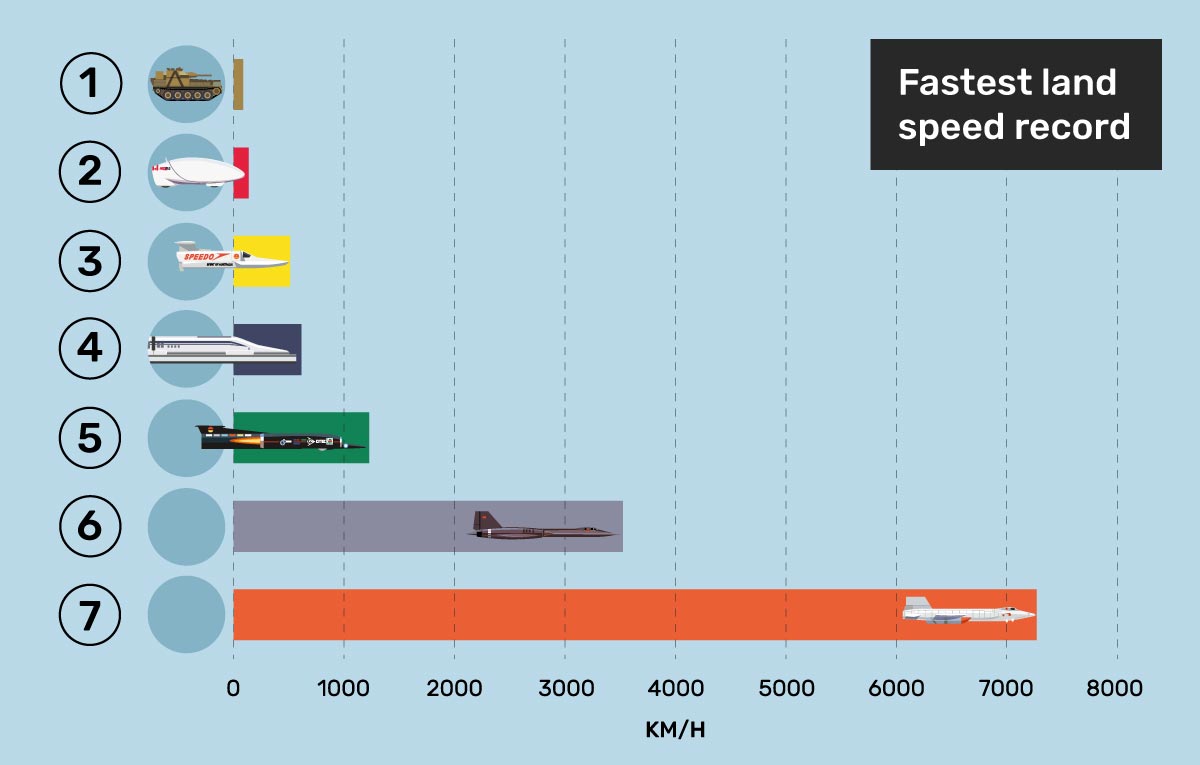

A need for speed: more record-breaking vehicles

Andy Green appears in Guinness World Records 2021, out now in shops and on Amazon.