‘Never again': a look back on first automobile fatality that killed female scientist

Ever since Mary Ward was a young girl, she was obsessed with science and innovation. She started collecting butterflies at age three, and the walls of her house in Ballylin, Ireland, were covered in glass cases of pinned insects and dried flowers gathered from nearby peat bogs and meadows. She wrote stories about bugs with her sister Jane, and in 1835 at age eight she spied Halley’s Comet by herself through a tiny telescope and announced the revelation to the delightfully surprised audience at her parent’s dinner party.

For someone who truly appreciated the science behind the natural world and the potential in technological innovation, her sudden death under the wheels of an early automobile – making her the unfortunate victim of the first road traffic death in the world – proved devastating for her family and for the scientific community at large.

Born Mary King in 1827 to the Reverend Henry King and his wife Harriette, Mary was educated at home with her sisters like most women at the time – however, she came from a renowned scientific family, who instilled her with a natural curiosity for the outside world.

Her family always encouraged her to pursue science, even though at that time many barriers prevented women from formal education or being acknowledged for their discoveries. But Mary dedicated days to drawing insects under the glare of a magnifying glass, until the fateful date when astronomer James South recognized her talents and persuaded her father to buy her a high-powered microscope. He spent £48 12s 4d, about £6,200 ($7,700 USD) in today’s money, and the rest was history.

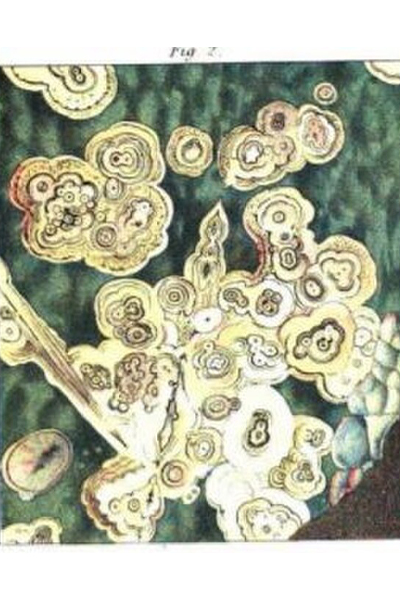

Hunched over, with her hair pulled back, Mary spent hours over the microscope, which was a new instrument at the time that opened worlds to the young scientist. She obsessively studied the minute details of plants and animals, sketching everything from crickets to cod eyes. She taught herself everything she needed to know about the tool, and even prepared her own specimens and made her own slides from slivers of ivory, as glass was difficult to obtain.

Despite the closed doors for female academics at that time, Mary was aided by her cousin William Parsons, the 3rd Earl of Rosse. He shared her passion for science, and she would make frequent stops to his Birr Castle to sketch his Leviathan of Parsonstown, a telescope with a six-foot long mirror which was the world’s largest until 1917.

Parsons also was made President of the Royal Society in 1848, and he used his position to introduce Mary to all the literary and scientific lions of the age. She would write to them often about their publications, and even became one of three women on the Royal Astronomical Society’s mailing list (the others being astronomer Mary Somerville and Queen Victoria).

She summarized her early research in her first book in 1857, Sketches with the Microscope, which showed close-up the anatomies of bugs and offered advice for using the instrument. Because of the barriers against female authors at the time, Mary believed nobody in Ireland would pick up her manuscript, so she privately published 250 copies. To her surprise, the opposite happened – the book sold out in a few weeks, and was reprinted eight times between 1858 and 1880 under the name A World of Wonders Revealed by the Microscope – and according to one historian, “did as much to make the microscope popular as any other book of the time.”

One of Mary's up-close sketches in an article by Sir David Webster. Photo credit: Wikimedia Commons

She went on to write a number of books about microscopes, telescopes, and the natural world, establishing herself as a respected member of the scientific community. She was also a beautiful painter, who illustrated all her own books, and was even hired to illustrate the biography of Sir Isaac Newton. Along with her cousin William, they provided significant research into the natural world and made significant contributions to Victorian science.

Which perhaps is why her death at the hands of the technology she so revered, is so difficult to comprehend.

By her early 40s, Mary had lived a fulfilling yet tiring life. Throughout all her scientific achievements, she was still tied to the social expectations for women at the time, and in 1854 she married aristocrat Henry Ward and gave him eight living children from 11 pregnancies in 13 years of marriage.

Her husband was the second son of a Viscount, and while he inherited his father’s entitled nature, he did not inherit his estate. He spent days idling by while Mary tended to the house alone because they couldn’t afford help, and she provided their only source of income from her writing. Their finances were tight, and by August 1869 Mary was burnt out, so she went to visit her cousin William at her happy place in Castle Birr to rest.

At the castle, William had one of the world’s first automobiles, a heavy, steam-powered machine with three thick iron wheels assembled like a tricycle to navigate the bumpy country roads. Always a lover of machinery, when someone suggested they take the car out, Mary agreed and joined her husband Henry, her two teenage cousins, and their tutor, for a fateful ride.

Photo of a Rickett's steam-engine powered car in the 1860s, a similar vehicle ran over Mary. Photo credit: Alamy

They decided to circle the town green, and approached a church “at an easy pace,” as the speed limit was only 7 mph (11 km/h) at the time. According to a witness, they were only travelling at 3.5 - 4 mph (6 km/h). It’s hard to know what happened next, but as the car took a turn, the vehicle jolted, and Mary was thrown from her seat on to the street. Before the driver could stop, her head was crushed under one of the heavy wheels, and broke her neck and jaw. A local doctor rushed to the scene, but couldn’t save the scientist, and she died within minutes.

A newspaper article published in the King’s County Chronicle on 1 September 1869, the day following the accident, read: “The utmost gloom pervades the town, and on every hand sympathy is expressed with the husband and family of the accomplished and talented lady who has been so prematurely hurried into eternity…The Hon. Mrs. Ward was a lady of great talent, and accomplished in literary and scientific pursuits.”

The news of a bright life snuffed out early shocked the community (and the world), as many already distrusted this dangerous new technology. Although an inquest cleared everyone from charges for the tragic accident, the devastated family ended up dismantling the car and burying it under the castle, while leaving Mary’s scientific tools on display in her memory. At the inquest, the presiding coroner, John Corcoran, stated "this must never happen again."

Perhaps one of the greatest ironies about this tragedy was that a decade later, her husband’s older brother died, leaving the wealth of the family in her husband’s hands and allowing the remaining members of her family to live out their lives in peace. If she had lived, she might have been able to have a lab of her own, and could have followed her passions instead of her duties.

Mary, photographed before her death. Photo credit: Wikimedia Commons

And while her life is often overshadowed by the nature of her death, the Road Safety Authority (RSA) in Ireland is trying to use Mary’s memory to prevent similar tragedies from happening in modern day. As we are all aware, car accidents are one of the leading causes of death, and it seems surreal to think that this unfortunately familiar tragedy first started with Mary.

The campaign’s goal is to end road traffic deaths in Ireland, by creating lesson plans and a book that flicks past page after page filled with the thousands of names of those lost on our roads in the years since Mary. Their goal is to humanize those who are a part of this staggering statistic, by sharing the story of Mary and other victims.

“Our new TV and radio campaign ‘Who was Mary Ward? Vision Zero’ raises awareness of the fact that the first person in the world to die in a road crash happened here in Ireland and thousands more have lost their lives on our roads since then,” says the campaign. “This is not about shifting the responsibility to road users. We are all in this together.”

Header image: Alamy