Inside a Canadian professor's 43-year-old Dungeons & Dragons campaign

On 25 April 1982, two teenage boys in the small town of Borden, Saskatchewan, Canada began playing the relatively new fantasy role-playing game Dungeons & Dragons. Within the fantasy world being developed, a young warrior and adventurer by the name of Titanius Baldwinov set out from the burned ruins of his village in Greyhawk, looking for revenge. On his travels, he would fight beasts in the foothills of the Drachensgrab Mountains, hunt for hidden treasure in caves, and do what he could to survive in the violent and dangerous land.

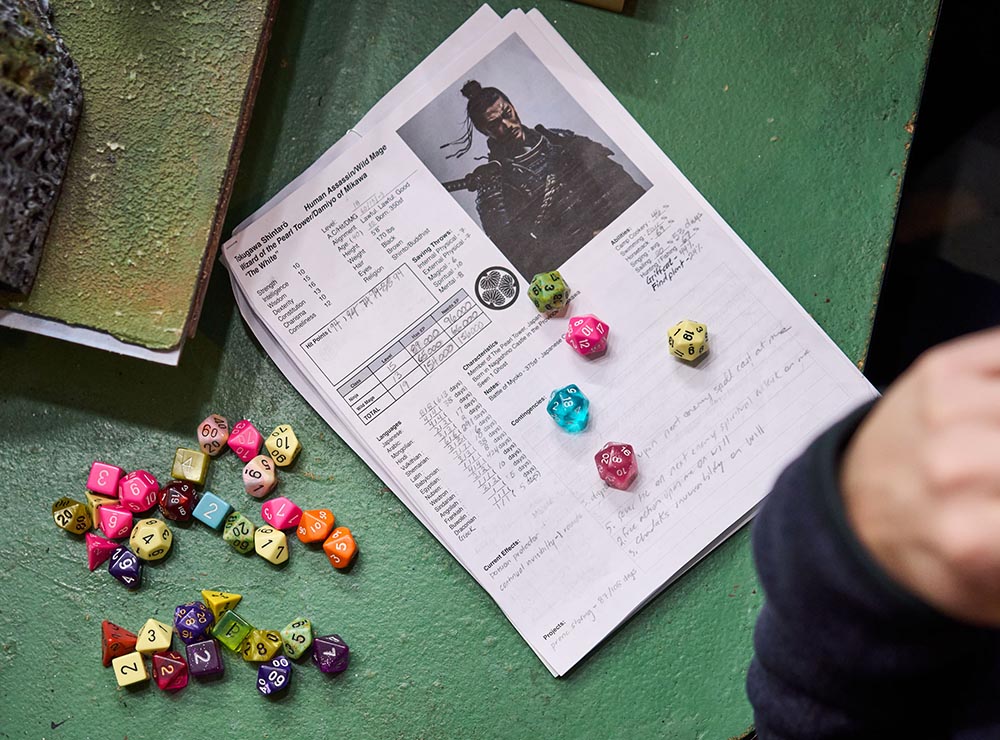

Titanius's fate was guided by Jeff Golding – who was playing the young fighter – and Robert Wardhaugh – who was in the role of Dungeon Master (or DM). The graph paper maps, character sheets, dice, and printed adventure modules and rule books (from TSR - the company that developed Dungeons & Dragons) were laid out wherever the two boys could find a place to play.

The game they played was a lot of fun, and they decided to keep going with the campaign. Over the next few months, more players joined Robert's game. Titanius met the thief Conan Blackrazor, the wizard Elrond Miltonov and the cleric Arak. These adventurers joined forces as the "Party of the Pendant", and their players became devotees of what they called simply "The Game".

Today, 43 years later and more than 2,000 km away, Robert Wardhaugh's D&D campaign is still going strong. The Dungeon Master, who is today also a history professor at the University of Western Ontario, is the proud holder of the GWR title for the longest running D&D campaign (homebrew).

He estimates that around 500 player characters have passed through the ranks of the Party of the Pendant over the last four decades, which corresponds to over four centuries of in-game time. Characters have come and gone, empires have risen and fallen, magical items – taken from cursed tombs or dragon's hoards – have been handed down through generations of player characters. Despite all the changes in Robert's life and those of his many players, The Game – as they still call it – has endured, never going more than a couple weeks without a session, and typically doing two or three sessions a week.

So how has Robert kept The Game going for so long, and what makes it so special?

1. Spectacle

It's hard to overstate Robert's dedication to the Dungeon Master's art. The entire basement of his house – which he picked because it met The Game's needs as well as his family's – is dedicated to Dungeons & Dragons. In addition to the large room where sessions are held, there is also a model-painting workshop and storage rooms that contain every setting a storyteller might need.

This includes huge modular town sets, each representing a different historical period or culture; terrain for everywhere from barren deserts to snow covered mountains; and grand set-pieces such as ancient ruined temples, gladiatorial amphitheatres or castles.

Robert estimates that he has around 30,000 hand-painted miniature figures, allowing him to set up encounters with everything from a horde of puny kobolds to a towering multi-headed dragon.

2. Pacing

Robert's priority is keeping his players interested and engaged. As Dungeons & Dragons is a turn-based game, that means he emphasizes speed and action, moving from one player to the next as quickly as possible. When he started out, he was using the (1st and 2nd edition) rules laid out in Advanced Dungeons & Dragons but he quickly found that traditional rule-set slowed things down too much.

Taking the advice of AD&D's introduction (written by the game's co-creator Gary Gygax), Robert started modifying the rules to suit his own game. He dropped things that slowed down combat, created his own systems for levelling characters and – as the scope of his campaign grew – started adding new character classes, new enemies and new gameplay mechanics. These changes (which have been made in parallel with the shifting rules of D&D's official releases) are the reason for the qualifier "homebrew" in the record title (a term used to describe DM-specific rule changes).

3. Flexibility

After Robert left Borden to go to university in Saskatoon in 1985, the original Party of the Pendant grew to include a rotating cast of players. Not everyone attends every session – at the moment there are around 60 active players involved in The Game, but generally sessions only involve five to eight players at a time.

Robert has developed a number of ways to keep his players engaged, even if they can't play for an extended period. Each session, a party report is written by one of the players, that is then sent out the others. A massive website has been developed containing decades of information and material. Players are often flying into London, Ontario (the present home of The Game) for gaming trips. Players are now able to participate online from anywhere in the world.

If players have to step away from The Game for an extended period, Robert will keep track of their characters, quizzing players on what their character has been doing while they were away from the action. Characters can train or study to improve their skills or teach things to their in-game children. Long-standing players now have family trees extending over fifteen generations.

4. Player Freedom

Because Robert has been running The Game continuously for more than four decades, he knows the setting inside and out (being a history professor helps develop the world and its many cultures). Adventures take place in a world that is based on real-life historical Earth, but one that has been altered into a fantasy setting that includes orcs and dragons. Characters that travelled to England, for example, would find themselves in the land of Arthurian legend, while Viking Sagas or Roman mythology might dominate elsewhere.

His familiarity with this fictional world means that he doesn't generally have to do much – if any – specific prep for sessions. Robert prefers to react to whatever his players decide to do as the events he describes unfold, and he abhors the dark art of "railroading" (pushing players towards specific actions and outcomes that fit with a DM's planned narrative).

5. Longevity

The simple fact that The Game has been going on for so long gives it a depth and breadth that no other campaign can match. Robert has decades (or centuries, in-game) of lore and history to draw on, a massive cast of established characters, countries and factions with their own agendas and alignments. A demon lord banished a century ago (or a decade in real time), for example, might be summoned back and unleashed once again on the material plane, testing old alliances and bringing a new generation of heroes out into the world.

Robert plans to keep going with his campaign for as long as he is able. The grand overarching narrative of his setting – the growing threat from a mysterious entity that his players know only as "The Arriver" – still has plenty of life in it (he's been building this conflict up since the early 1990s), and his players' decisions constantly push the game in novel directions that inspire new storylines.