Peggy Whitson: Most spacewalks by a female

There's no getting around the fact that space travel has long been a male-dominated field... But this farmers' daughter from Iowa wasn't afraid to look up at the night sky and dream... and went on to become one of the most successful - and respected - astronauts of all time.

You might be surprised to learn that nearly 90% of all astronauts have been men. But the stellar achievements of inspirational figures such as Peggy Whitson (USA) is helping to redress that balance. During a long and distinguished career at NASA – which saw her pick up four Exceptional Service Medals, alongside a host of other awards for scientific achievements – this experienced biochemist racked up a string of GWR titles. Between 2002 and 2017, she made 10 extravehicular activities, or spacewalks, around the International Space Station (ISS), an unprecedented feat for a woman and one still unsurpassed.

She remains an icon for aspiring female astronauts everywhere.

Eyes on the skies

Peggy Annette Whitson was born on 9 Feb 1960 in Mount Ayr, Iowa, USA. Her parents were farmers, but any thoughts Peggy might have nurtured of following in their footsteps were abandoned on 20 Jul 1969. That night, along with millions of TV viewers worldwide – she watched as Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin (both USA) became the first people on the Moon. Although she was only nine, Peggy was fascinated by the idea of people actually working as astronauts for a living.

Further encouragement came in Jan 1978, the year Peggy graduated from high school, when NASA’s first female astronauts started training, who included among them Dr Kathryn Sullivan, a fellow record-setting astronaut. To Peggy, it provided joyous confirmation that spaceflight was no longer the exclusive preserve of male astronauts. Among the six women chosen was Sally Ride, who would become the first American woman to fly in space five years later.

In this respect, at least, the USA’s great rivals in the Space Race were literally decades ahead. Twenty years previously, on 16 Jun 1963, Soviet cosmonaut Valentina Vladimirovna Tereshkova (USSR) had become the first woman in space, when she launched in Vostok 6 from the Baikonur Cosmodrome in Kazakhstan.

I think the biggest advice that I could give people is to actually try and live beyond your dreams by pushing yourself, challenging yourself to do things a little bit outside of your comfort zone

- Peggy Whitson

Role models & mentors

One of Sally Ride’s fellow recruits was Shannon Lucid, a trained biochemist, and her presence made a lasting impression on Peggy, whose aptitude for the sciences had become increasingly evident through her school and college years.

That natural talent was fostered by a string of invaluable mentors. “When I got to college, I had a phenomenal advisor, Dr Delores Graff… who just had so much energy and enthusiasm for science,” she told website Brilliant Star in 2019. “It was just kind of intoxicating just being around her. I then got my PhD, and Dr Cathy Matthews was my advisor… a powerhouse of a woman who really could do anything she wanted in her field of science.”

Peggy received her doctorate in biochemistry in 1985 from Rice University in Houston, Texas, USA. The following year, she joined NASA’s Johnson Space Center (JSC) as a research associate. There, she met another inspirational figure, Dr Carolyn Huntoon, who gave her the chance to develop her leadership skills. All that support and encouragement was pivotal in empowering her, as she enthused to Brilliant Star: “For the young people out there, if you don’t have somebody like that, you need to find somebody.”

Long road to the launch pad

Over the following years, she worked in a range of different roles for NASA, from supervising a biochemistry research group to becoming deputy chief of JSC’s Medical Sciences division. She also worked on collaborative projects between US and Russian scientists, and would go on to become project scientist for the Shuttle-Mir Program. But she faced her share of knockbacks too. In fact, her applications to join NASA’s astronaut programme were rejected for 10 long years before she was finally accepted in 1996. The time she’d spent working with Russian scientists, sometimes in Russia, proved to be her winning ticket, for NASA was recruiting personnel to work on Russo-American projects on board the ISS. In August of that year, she began her training.

Peggy first flew to the ISS herself on 5 Jun 2002 with the Expedition 5 crew, a mission that had been three years in preparation. She started as a flight engineer, but was duly appointed as the space station’s first NASA science officer.

She conducted experiments into microgravity and human life sciences and also made her very first spacewalk, or extravehicular activity (EVA), during which she fitted a service module with shielding among other tasks. “When I first flew in space we were still pretty much assembling the space station,” she explained to GWR, “so the majority of our time was spent on that.”

Peggy takes command

Rising through NASA’s ranks, the following year Peggy became deputy chief of the Astronaut Office. By 2005, she was training as back-up commander for the ISS. On 10 Oct 2007, she flew into space for the second time as part of Expedition 16. This time, she had the added honour – and responsibility – of becoming the first female commander of the ISS. She held the post until 8 Apr 2008, but would resume it on 10 Apr 2017 for Expedition 51.

During her six-month tenure on that mission, Peggy oversaw an expansion of the crew’s workspace and living quarters, and made a further five spacewalks to work on the ISS. “It’s a huge vehicle,” she told GWR in 2017, “and it’s been up here for 17 years and we’re trying to develop new systems, so things have to be worked on and upgraded all the time.” Those open-space excursions are extremely demanding.

Peggy’s longest-ever EVA lasted for more than 8 hr, and during that time she had to carry out complex tasks and manipulate tools, working herself along rails on the outside of the ISS, all the while coping with the pressure of her own space suit. Moreover, astronauts have a set time period within which to carry out their operations. And although spacewalking astronauts carry water inside their space suits, they are without food for the duration of the EVA, so they stock up on carbohydrate-heavy dishes before venturing out.

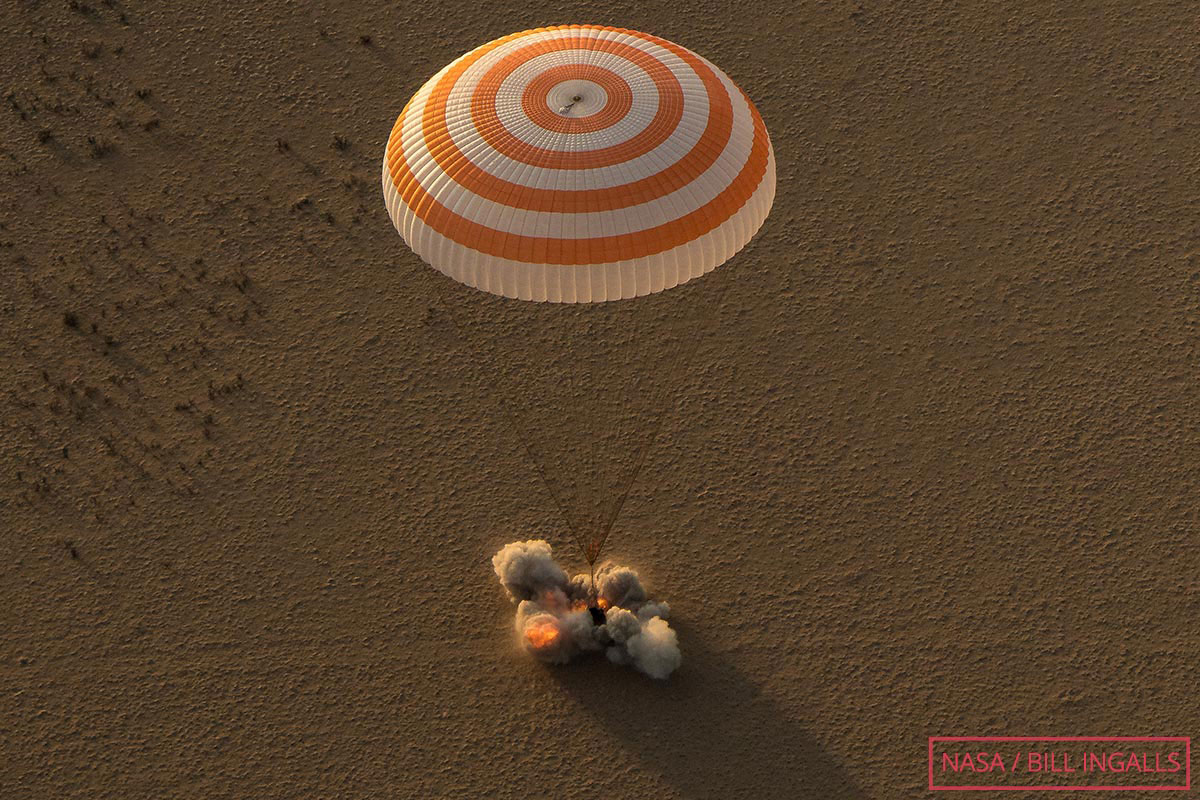

The flight back to Earth, on 19 Apr 2008, proved unexpectedly eventful – and not in a good way. Peggy and the rest of the crew were on board the same Soyuz TMA-11 spacecraft the previous October, but a failed separation between two modules forced the craft into a precipitous return trajectory – known, rather alarmingly, as a “ballistic re-entry”. It ended in a jarring landing some 300 mi (470 km) from the intended touchdown spot, though the crew emerged safely.

Q&A with Peggy Whitson

Now you are a role model yourself. What do you hope to inspire in people following in your footsteps?

What does it feel like to be a multiple record-breaker?

So, as we speak to you, you’re floating in zero gravity. Is that still fun or is it just “another day in the office” now?

Is training to be an astronaut as hard as it seems?

So are you fluent in Russian now?

What is a typical day like for you on the ISS?

Is there any research you get particularly excited about when you’re about to embark on a mission?

Is there anything you would love to discover/achieve as you continue space travel?

The final missions

By 2009, Peggy had become chief of the Astronaut Corps, organizing preparation and support for ISS crews. She was the first woman ever to hold that role. It would be a full seven years before she returned to the ISS and when she set off from the Baikonur Cosmodrome at 2:20 p.m. CST time on 17 Nov 2016, she became the oldest female astronaut, aged 56 years 282 days.

During the course of her stay, she made a further four spacewalks to maintain or swap out components on the ISS. On 23 May 2017, during the Expedition 52 mission, she made her 10th EVA, which remains the most spacewalks by a female.

GWR spoke to Peggy during a live interview during this, her final mission. In a comment that has taken on a new relevance since the world went into lockdown over COVID-19, she told us, “In terms of illness, because we live in a pretty isolated environment up here, we don’t really get sick for the most part.

"We actually quarantine our crews for one or two weeks before launch to try and prevent us bringing up cold germs or the flu or other illnesses. And it seems to work well – none of us have been sick!” (For more revelations from space, see Q&A above.)

On 3 Sep 2017, Peggy returned to Earth (below), landing in a remote part of Kazakhstan with astronaut Jack Fischer – her partner on her final two spacewalks – and cosmonaut Fyodor Yurchikhin.

Passing on the baton

Over the course of her illustrious career, she had now spent 60 hr 21 min on EVAs for the ISS in all, the most accumulated time on spacewalks by a female. What’s more, the 289 days 5 hr 1 min she’d spent in space on this, her final mission, also represented the longest continuous time in space for a female astronaut, up to that point. That record was subsequently broken by Christina Koch (USA), who has now racked up a duration of 328 days 13 hr 58 min.

Peggy had mentored Christina – just as she herself had benefited from accomplished older female guides earlier in her career. And when her protégée broke her record, on 28 Dec 2019, she offered her warmest congratulations. In zero gravity, appropriately enough…

I honestly do think that it is critical that we are continuously breaking records, because that represents us moving forward in exploration

- Peggy Whitson

Peggy retired from NASA on 15 Jun 2018. It’s a mark of her stature that TIME magazine included this pioneering figure in its annual list of the 100 most influential people.

In a tribute, ESA astronaut Pesquet stated “ I could only imagine the challenges she had to overcome, moving from a farm in rural Iowa to academia to the International Space Station, cracking through the glass ceiling with every step.”

And every crack – from this iconic space pioneer and those she has inspired – creates more room for young female astronauts to break through.

Peggy Whitson appears in Guinness World Records 2022, out now in shops and on Amazon.